It’s one of the biggest sovereign bond defaults of 2022, if hardly unexpected: Ghana announced Monday that it would no longer service most of its external debt, including all payments due to private-sector bondholders and other lenders.

Why it matters: There’s often a very long gap between the point at which default becomes inevitable and the point at which it actually happens. (Venezuela sat in that gap for years.) Ghana seems to have decided that if you’re going to do it, you might as well do it early.

The big picture: Ghana recently agreed to a program with the IMF whereby it will borrow $3 billion. (Debts to the IMF and World Bank are not included in the standstill; neither are any debts incurred after today.)

- The IMF doesn’t want that $3 billion to go to foreign creditors — quite the opposite. It wants foreign creditors to do their part in reducing Ghana’s debts and made the $3 billion contingent on Ghana reaching an agreement with its foreign creditors. Announcing a standstill is the hardball way of trying to get such an agreement.

Between the lines: Broadly speaking, debt restructurings can be “market-friendly” or “coercive.” A market-friendly restructuring happens after negotiations; a coercive one normally happens after the country has already defaulted and creditors are receiving nothing. Ghana’s decision on Monday means they’ve decided to go the coercive route.

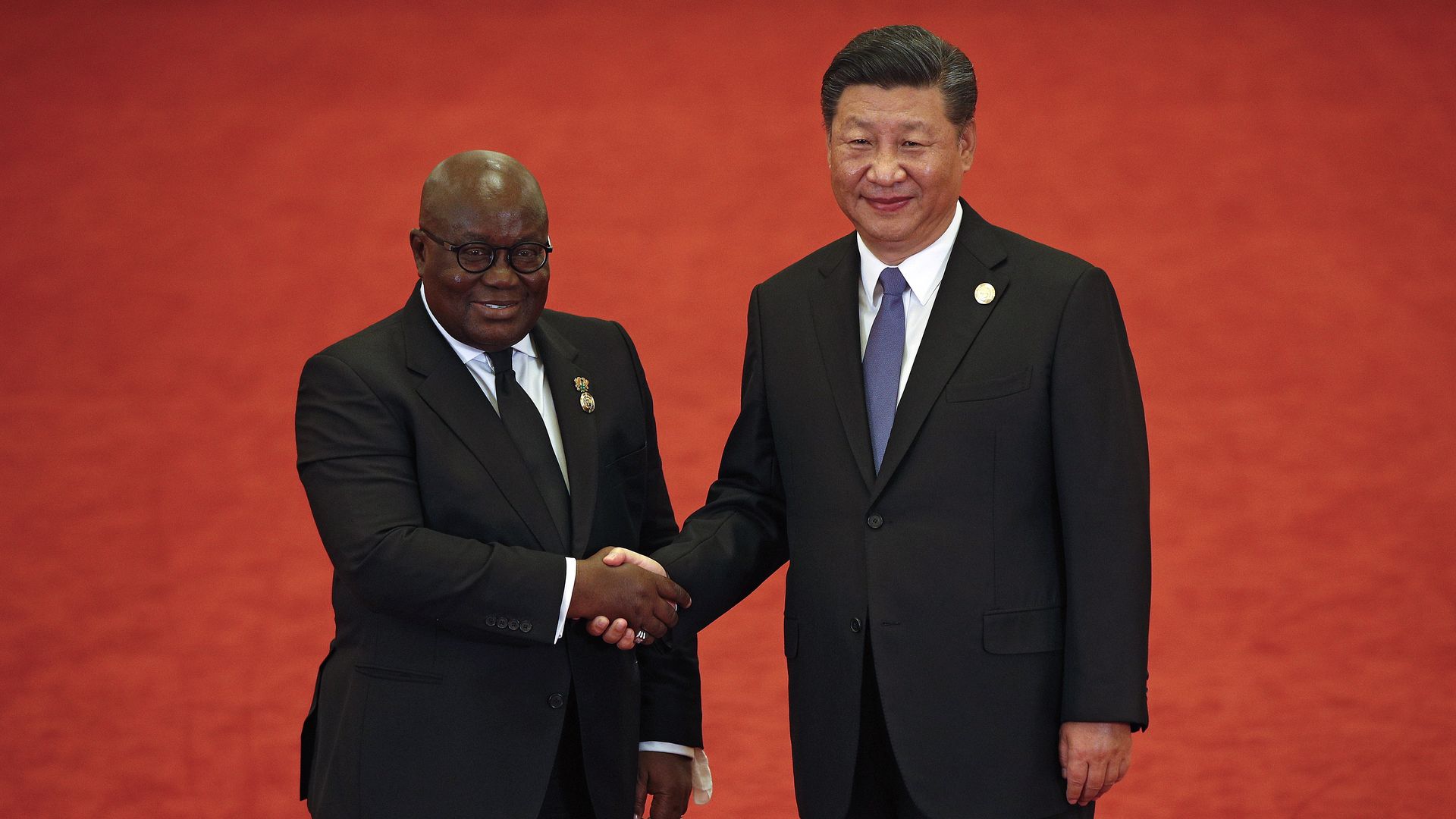

What we’re watching: Ghana owes China some $3.5 billion. That could be the stickiest debt of all to restructure — and the other creditors are unlikely to take a deal for anything less than what the Chinese receive.

The bottom line: Ghana’s debts will be restructured eventually, but don’t hold your breath. This one could take a while.

Original Source: Axios